A Peculiarly British Noir

- plecomber

- Aug 14, 2025

- 3 min read

As well as consuming a wealth of films, social history books, and crime exposés, I drew great inspiration for my Golden Age crime series, Piccadilly Noir, from a collection of written works with a distinctly local provenance. After all, unlike the American milieu of Chandler’s and Hammett’s detectives, my protagonist George Harley inhabits a peculiarly British world – a world of grubby bedsits, all-night cafés, egg and chips, and Gold Flake cigarettes (just think of Pinkie in Brighton Rock, brushing the stale sausage roll crumbs from his bed, and you’ll get the idea).

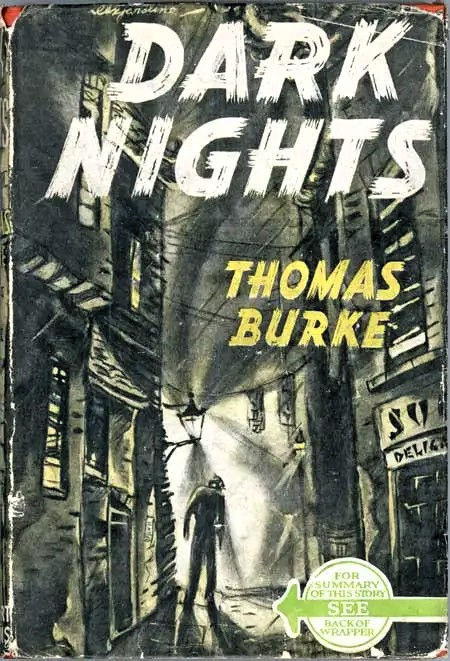

To provide the base flavour I began with some London aromatics. Dickens, of course, especially in his Sketches by Boz phase, offering those glorious vignettes of Victorian street life, peopled with caricatures dashed off like one of those street-pitch tourist cartoons, yet immediately springing to life on the page. The travel writer H. V. Morton’s intimate portrait of the city, In Search of London. Thomas Burke, whose problematic racial stereotypes might nowadays obscure his otherwise fascinating work – particularly in collections such as Dark Nights and Night-Pieces, and in his wonderfully-observed novel Victorian Grotesque, set in the plebeian wonderland of the music halls. And, of course, that great biographer of London, Peter Ackroyd.

To bring out the period flavour of the interwar years, I turned to Patrick Hamilton’s Twenty Thousand Streets Under the Sky, which – with its petrichor of disappointment and its cast of troubled sex workers and bored bar staff – formed a rich stock for my historical world-building. I then added a glug of his Hangover Square, and a spoonful from Alexander Baron’s mustard-pot of a novel, King Dido (which, though not set in the period, nonetheless added depth with its vivid depiction of a struggling working class). Further complexity of flavour was provided by Norman Collins’ London Belongs to Me, Simon Blumenfeld’s Jew Boy, and Arthur Morrison’s A Child of the Jago – as well as by the more obscure Storm Jameson’s Here Comes a Candle, Philip Allingham’s Cheapjack, and Hippo Neville’s glorious Sneak-Thief on the Road.

Now we come to the meat and veg of this literary stew: the works of the great Gerald Kersh – chiefly Night and the City, but also Fowler’s End, Prelude to a Certain Midnight, and The Angel and the Cuckoo. Now sadly mostly forgotten, Kersh was once among the highest-paid writers in Britain. He wrote nineteen novels and over three thousand short stories – this during the golden age of the form, when prestigious magazines in both the UK and US paid handsomely for content. Before turning to writing, he lived a life worthy of one of his own colourful characters – he’d been a minder, cinema manager, cook, sales rep, and wrestler. He served in the Coldstream Guards in WWII and attended the liberation of Paris as a war correspondent. A blend of Kersh’s Night and the City and Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock was exactly the flavour I was aiming for when I first set out to create George Harley’s world.

But the mix still needed a little extra spice. For that, I turned to a selection of gritty 1930s novels, including James Curtis’ The Gilt Kid and They Drive by Night; Robert Westerby’s fabulously-titled Wide Boys Never Work; and Grierson Dickson’s Soho Racket. Alongside a collection of contemporaneous slang dictionaries, these books helped shape the colourful vernacular of my characters’ dialogue.

And so, I thought, I had the perfect recipe for a hard-boiled British noir series, set in the underbelly of London in the 1920s–30s. But on a final tasting, I discovered that a dash of Dennis Wheatley had somehow slipped into the pot, and my cockney detective found himself up against a clandestine occult society straight out of The Devil Rides Out. Ah well, I grew up in the 1970s – some influences are obviously subconscious. As a writer, I guess you’re never fully in control of that creative process.

A shortened version of this article first appeared on Martin Edwards' blog:

Comments